How Pharmaceutical Systems Strengthening Benefits Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Care Services

By Jane Briggs, USAID MTaPS, and Patricia Jodrey, USAID

Global trends in maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) had been increasingly positive; for example, worldwide, maternal mortality dropped by 34% from 2000 to 2020.[1] Unfortunately, the pandemic set progress back significantly, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[2] Shockingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, almost 95% of maternal deaths in 2020 were in LMICs, and globally about 800 women died every day during and following pregnancy and childbirth from preventable causes.1 A staggering 5 million children died in 2021 worldwide—9 per minute—and around 700,000 died from pneumonia and other treatable respiratory infections.[3] As a result, strengthening MNCH services remains a country and donor priority that relies on access to quality and safe lifesaving medicines. Equally important, women and children’s caregivers must actually seek out the health services, which happens less often when clinics are stocked out of medicines.[4] Therefore, investments in MNCH programs must focus on strengthening both supply and demand for quality health services and products in a virtuous cycle. It is insufficient to focus merely on supply chain and logistics challenges, because while important, they do not influence all dimensions of access to lifesaving treatment. Access includes affordability, acceptability, and accessibility in addition to availability. Furthermore, the products need to be safe, effective, of quality, and used appropriately. We therefore think it is necessary to invest in all aspects of the pharmaceutical system, not just the supply chain, from improving registration and procurement processes to ensuring that women and children receive appropriate lifesaving treatment and use it appropriately.

National health agendas often neglect to address the limitations and challenges to ensuring the availability and quality of essential MNCH medical products, policies to facilitate access to medical products may be inadequate, and financial resources are limited, resulting in limited availability and poor management of essential MNCH medical products. Countries need to make the pharmaceutical system a priority and call on donors and development partners to contribute to strengthening the pharmaceutical system rather than supporting selected components or creating parallel systems. MTaPS has been supporting countries to strengthen their pharmaceutical systems and improve access to and appropriate use of quality-assured medicines for MNCH services in various ways, including streamlining product registration, promoting promising subnational procurement practices, identifying methods to better engage civil society, and working with health care providers to improve the use of MNCH medicines such as amoxicillin and magnesium sulfate. More examples of MTaPS’ pharmaceutical systems strengthening work and its benefits for MNCH are presented here.

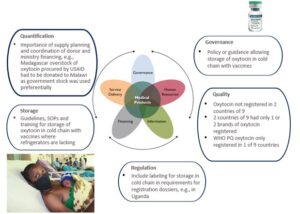

Figure 1: Example of pharmaceutical systems strengthening[5] as it relates to oxytocin, a key MNCH product to prevent and treat postpartum hemorrhage.

Registration Challenges that Compromise MNCH Commodity Availability

An inefficient registration process can limit the availability of critical MNCH medical products in several ways.2 For example, it may slow the market entry of innovative products and the registration of quality-assured generic products, including those prequalified by the World Health Organization (WHO), which may leave a void that substandard or falsified products can fill. MNCH medicines have especially low profit margins due to their ease of production and variety of manufacturers, which, along with an inconvenient registration process, are disincentives for manufacturers to invest in increasing quality processes to bring these products up to standard.

To identify current barriers, we assessed the registration status of 18 MNCH tracer medicines in 9 countries by reviewing policies, regulations, and other technical documents and by interviewing each country’s regulatory authority and 11 pharmaceutical manufacturers of MNCH medicines.[6] We found that most countries had registered most of the tracer medicines but that the percentage of medicines with at least one registered product was as low as 28%. Some countries had only one or two registered MNCH products, leaving them vulnerable to supply chain shock, while the average registration timeline ranged from six months to four years due to registration backlogs and complicated procedures. Furthermore, countries were not taking advantage of strategies to streamline product registration. These include authorizing regulators to formally incorporate recognition, reliance, and risk-based regulation in their legislative frameworks and prioritizing the registration of products of public health benefit—including those for women, newborns, and children. National regulatory authorities can also improve registration efficiency by applying standardized good medicine assessment review practices and electronic assessment procedures.

Building on this mapping, the USAID Medicines, Technologies, and Pharmaceutical Services (MTaPS) Program supported Mozambique to open a dialogue between manufacturers and regulators to discuss challenges to registration and to build dossier reviewers’ capacity to assess bioequivalence data for oral generic medicines, such as amoxicillin dispersible tablets (DTs), to ensure their quality and register them more quickly. In addition, we are supporting the Southern African Development Community (SADC) to prioritize and streamline the registration of MNCH medicines. A regional team conducts a joint assessment that SADC member countries can use in their registration process rather than assessing products from scratch themselves. Electronic regulatory management information systems are being introduced in several MTaPS countries, including Nepal, Mozambique, and Rwanda, to increase the efficiency of the registration process, including for MNCH medicines.

Subnational Procurement of MNCH Commodities in the Public Sector

Typically, it is the national government procurement and supply agency rather than the donor’s procurement mechanism that is responsible for making quality essential medicines, including MNCH products, available and affordable, as donors typically procure few if any MNCH medicines. However, public supply systems’ poor performance often leads to stock-outs at health facilities, which then fill the gap through local private suppliers. For example, Nigeria’s public health facilities frequently purchased reproductive health and MNCH commodities from the private sector due to the public sector’s unreliable procurement and supply system and the private sector’s cheaper prices and better delivery services.[7] In response to political reform or problems with centrally controlled supply, many LMICs have decentralized the procurement of health commodities to the province, county, district, or even facility level. However, if the procurement process does not integrate good procurement principles, including alignment with the WHO model quality assurance system that covers product and supplier prequalification, purchasing, storage, and distribution,[8] prices, services, and product quality suffer. Our 2022 study of subnational procurement of MNCH medicines in Nepal, for example, found widespread use of direct purchasing and weak procurement methods that resulted in a wide range of prices—with the lowest levels of the health system generally paying the highest prices.[9]

We published guidance summarizing core objectives of good procurement practice that describes three mechanisms that countries can use to operationalize good procurement practice elements—framework agreements, prime vendor programs, and e-procurement systems—with detailed examples of how countries have used these mechanisms to provide quality-assured medical products at lower cost.

Engaging Civil Society through Social Accountability to Improve Access to MNCH Medicines

Poor accountability in the health system weakens MNCH services, including access to quality medical products, and discourages demand among women and caregivers.[10] MTaPS developed a discussion paper summarizing key action steps for donors and program implementers that reviews lessons learned in engaging civil society through social accountability approaches in health, particularly for MNCH; identifies the lessons’ implications for policy and practice; and exemplifies how the lessons improve civil society engagement and social accountability around MNCH medical products.

Although many social accountability tools and approaches are available, interventions still do not reach their potential. Effective social accountability interventions must be designed for the accountability ecosystem in which they operate. By following these steps, donors and implementers will be more likely to invest in and design interventions that substantially and sustainably improve access to and use of quality MNCH medical products. We hosted a knowledge exchange for USAID MNCH implementing partners to share best practices and promote the approaches described in the MTaPS discussion paper.

Improving the Use of MNCH Essential Products to Save Lives

Many times, health workers have access to MNCH products but their lack of knowledge of how to use them leads to unnecessary illness and death. This was illustrated in MTaPS’ work in Democratic Republic of Congo, where health workers were not managing common, fatal conditions such as postpartum hemorrhage, eclampsia, and pneumonia appropriately, even though the appropriate products (oxytocin, magnesium sulfate, and amoxicillin) were available. We collaborated with central and provincial officials to develop and distribute MNCH protocols and job aids at 170 facilities and community MNCH programs in Nord Kivu and Ituri provinces.

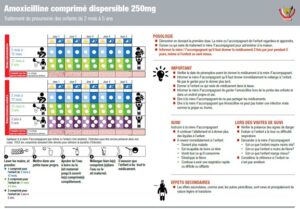

Figure 2: Job aid from DRC for health care providers on the use of amoxicillin for pneumonia

“We had lost many patients in the past due to a lack of knowledge and protocols/job aids to assist and guide the management of patients, especially the administration of medicines such as magnesium sulfate. For example, two pre-eclamptic women died due to the fact that health providers didn’t know how to use magnesium sulfate, whereas this product was available. But today, with the support from MTaPS, we can no longer make such mistakes and errors as we have all the needed guiding protocols and job aids.”—Dr. Patrick Basara, Head of Rwampara Health Zone in Ituri.

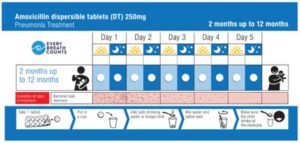

These issues also apply to pediatric medicines, leading to unnecessary deaths from easily treatable conditions. MTaPS, together with other partners, UNICEF, experts from the Child Health Task Force, and country stakeholders, published a call to action to improve the use of inexpensive, proven products such as amoxicillin and gentamicin to treat newborns and infants with pneumonia and other bacterial infections. Problem areas include poor quantification, storage, and use. MTaPS developed a for both caregivers and health care providers to increase adherence to proper treatment with amoxicillin DTs, which is WHO’s recommended treatment for pediatric pneumonia. The toolkit, which is available in English, French, and Spanish, contains dispensing envelopes to help caregivers give children the medicine correctly, leaflets describing times when amoxicillin suspension would be a better choice, and job aids to remind community and primary health care workers how to provide treatment with amoxicillin DTs and other important messages.

Figure 3: Example of dispensing aid for amoxicillin for caregivers

Conclusion

If we are to reverse the ground lost during the pandemic; regain momentum in reducing maternal, newborn, and child mortality rates; and meet the Sustainable Development Goals, the public health community needs to recognize the link between access to quality-assured MNCH products and health outcomes of women, newborns, and children. Health care workers need quality essential medicines to provide appropriate lifesaving treatment. Because access to these products requires strong and resilient pharmaceutical systems, we believe in the value of investing in all aspects of the pharmaceutical system, not just the supply chain, from improving registration and procurement processes to ensuring that women and children receive appropriate lifesaving treatment. Without essential MNCH products, we cannot expect to have good MNCH outcomes. MTaPS seeks to drive a shift in discourse from the role of MNCH medicines in national health systems as primarily an input commodity to the structures and processes within the broader health system that help ensure access to affordable, quality-assured MNCH medicines. We hope that this shift will be reflected not only in the norms, policies, guidance, and approaches being promulgated globally but also in the resources mobilized to support pharmaceutical systems strengthening.

[1] WHO. Maternal mortality fact sheet. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. February 22, 2023.

[2] Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Jun;9(6):e759-e772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. Epub 2021 Mar 31.

[3] UNICEF Data: Monitoring the situation of children and women. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/pneumonia/#:~:text=A%20child%20dies%20of%20pneumonia,of%20these%20deaths%20are%20preventable

[4] Favero R, Dentinger CM, Rakotovao JP, et al. Experiences and perceptions of care-seeking for febrile illness among caregivers, pregnant women, and health providers in eight districts of Madagascar. Malar J. 2022 Jul 7;21(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12936-022-04190-x.

[5] Refer to USAID’s pharmaceutical system strengthening approach: https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-systems-innovation/health-systems/strengthening-pharmaceutical-systems

[6] Briggs J, Kikule K, Walkowiak H, Guzman J. Improving Access to Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Products in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Considerations for Effective Registration Systems. March 2021. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the USAID MTaPS Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health, Inc. Available at: https://www.mtapsprogram.org/our-resources/improving-access-to-maternal-newborn-and-child-health-medical-products-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-considerations-for-effective-registration-systems/

[7] Nepomnyashchiy L., Prashant Yadav P. 2022. Decentralized Purchasing of Essential Medicines and Its Impact on Availability, Prices, and Quality: A Review of Current Evidence. CGD Working Paper 605. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/decentralized-purchasing-essential-medicines-and-its-impact-availability-prices-and

[8] WHO. 2014. A model quality assurance system for procurement agencies. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/medicines/norms-and-standards/guidelines/quality-control/trs986-annex3-who-model-quality-assurance-system-for-procurement-agencies.pdf?sfvrsn=275b3abc_2

[9] Dotel BR, Regmi B, Humagain B, Briggs J, Trap B. Subnational Procurement Practices of Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Medicines in Nepal. July 2022. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the USAID MTaPS Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health, Inc. Available at: https://www.mtapsprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Sub-national-procurement-mapping-report.Nepal_.July2022.pdf

[10] World Bank. 2003. World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People, Washington, DC.